1:1 Body Body Body

Look to the window, traveler. Where are you? You’ve awoken on a train going south, you know that much. There is no sun yet to melt away band of fog that lays across the land as thick and squishy as a Lucky Charms marshmallow. You wish you can tell this place apart from Indiana countryside, but you can’t. Does that upset the reptilian GeoGuessr part of your brain? You check your phone. Pehlinkavöy, Turkey. Oh, was that going to be your second guess after Indiana?

You’ve been sleeping in your cot since the border security stop. The officers were gruff but mild. You were told the Bulgaria/Turkey border is the third most securitized border after US/Mexico and North/South Korea, but that doesn’t sound right when you repeat it. At 2 AM in the security line, you found your Canadian friend Sabrina behind you. She was staying three doors down in your train compartment rationing her biscuits. You tell her about the fetishist, about your farmland rescue by a man named Angel, about the seminal 1999 dance-pop song “Mambo No. 5.” Your energy is not matched, but it is 2 AM. Both of you have gotten temporary lodgings in the New City of Istanbul, so you ride city transit after the overnight ends in the morning. A bus carries you across the Golden Horn, an inlet of the Bosporus and the first wide opening to see the city. Your bus rides through the arch of a Byzantine aqueduct and onto a bridge. You are surrounded by minarets, maybe a half a hundred, and just as many fishermen casting long lines off the bridge beside their planted ebikes or children, and twice as many sea birds, circling the waters around you just as they circled Tom Hardy in that great Istanbul montage you’ve seen again and again in 2011’s Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy. You need to limit that amount of times you reference this Gary Oldman picture—you’re scaring the hoes.

Does this bus remind you of any past buses? To be more specific, the Dubrovnik-Herceg Novi bus three weeks ago. Behind you were two intimidatingly French girls who took the exact route as you. When you exit in Herceg Novi, you tell them the local pub is having live music tonight at 9 PM. You do not attend, waylaid by escapades. Days later, see them in the Old Town of Kotor, standing by the walls, just absolutely demolishing a forth of a store-bought watermelon, juice and seeds running into the frantically torn cling-film. “We went to the pub and you weren’t there,” they say. Damn. When you compare routes, theirs is similarly eastward. You swap contacts, maybe you’ll meet in Bulgaria? You do not, they are going slightly faster than you. Which means they do give you tips about places as they leave and you arrive. Days before your arrival in Istanbul, they send you a Google Maps list developed by their new Turkish friend, Yigit Uckan. 47 places are marked with a 🌉, many with small notes. You decide to eat your way through as many as you can. This is one of the best decisions you could have made (see 1.6 for more).

No city on your trip can compare to Istanbul, that hits you very fast. The metropolitan area is far more populated than any place you’ve visited since New York—it’s larger than London, than Paris, than almost any European urban center. 16 million residents, and you are one, temporarily. You were taught in school that this was the administrative capital of the great Ottoman empire, that it was the crossroads of the world, but you can feel that on the street-level. On one avenue alone, you can see a clothing store themed around Buffy the Vampire Slayer, a door-to-door shipping company to Botswana, Zimbabwe, and Dubai, several clear views to the Mediterranean where cargo ships wait for their Strait passage, and shoe shops so dark and dense with animal-hide scents that in brings you back to Jesus in the lion's den. You have entered a truly vertical city. You can move in any axis you desire to great effect, up towards the minarets and hidden staircases that give you passage to dead-end lots, down to the backgammon players outside of corner stores beside the orange and watermelon juice sellers, or inward through the countless early modern arcades and interconnected alleys that make you feel like a cat instead of a tourist.

The city is expansive, dense, multicultural; anyone you pass could be from Istanbul. You could be from Istanbul. You are stopped several times for directions or advice, because you look Turkish, apparently. Aren’t you proud, looking like a local? You are stopped several times just to chat. Istanbulites are talkative in all forms—you’re surrounded with complaints, gossip, instructional hospitality, scams, and brief hellos. It feels incredibly Jewish to you, and puts you at ease. People are just people, at the end of the day. For the past month, you’ve been traveling from Venice to Venetian-Ottoman borderlands, to the Ottoman imperial core and if you’re being honest, Istanbul looks a hell of a lot like Venice. You want to ask why these two were fighting when they both have their pleasure-domes and love of seafood and a fashionable aristocratic merchant class, but that’s a self-defeating thought. In Sofia, Bulgaria, sirens blared one day as the entire city paused to mourn the anti-Ottoman Bulgarian revolutionaries. Cars stopped on the road. In Istanbul, not a single person brought up Bulgaria. There was no visible shared regional pride, many currency exchanges didn’t even trade Bulgarian lev. They share a border! They’re a day trip away! But the sense of scale is off, a flea on the back of an Anatolian dog.

You walk. With Sabrina, with your hostel group, or with your own whimsy, as far as you can. You keep wandering past centuries-old public fountains, for ablution or drinking, covered in Arabic calligraphic artwork. You pass Karaköy fish restaurants that look like refurbished ruins in an endearing way, with their low prices and vibrant washes of blue and green paint. For a country that has banned political protests, the amount of progressive and socialist postering surprises you, and you’re doubly surprised by how almost all of it is repurposed early 1900s Italian socialist ephemera. You worry you are making this city seem too crude, unkempt, or strange. But you trust you’ll be read with perspective and nuance.

Oh here, maybe highlight the Kia-Motors-sponsored reading nook outside the Zorlu Performing Arts Center, a place so annoyingly modern and lifeless that you could’ve found it in LA or London or Macau. There’s a line from your grandparents that you haven’t been able to excavate from your head for weeks. “Don’t worry Pearse, you can buy whatever you need on the trip. There’s a Sketchers store in Istanbul.” There’s a Sketchers store in Istanbul. None of those words were in the Bible. There shouldn’t be one, right? At least if globalization and filterworld standardizes all these world cities, shouldn’t it be more interesting than a Sketchers? So you’re in the Kia Motors reading nook browsing copies of The Economist, buying time until the concert you bought last-minute tickets to begins. Your seats are so shit that all staircases to your section are locked. Get fucked, right? No, they upgrade you twice for free, until you’re just behind the front row watching ANOHNI and The Johnsons sing experimental chamber pop. Between the performances, she projects interviews with coral reef scientists at the end of their careers, all struggling with climate grief and any morsel of hope. Then Anohni sings “Drone Bomb Me.” You never heard of this band before tonight, you know none of the lyrics, the tickets were $30 so it’s your Tuesday night in Istanbul.

“TK,” Anonhi says.

1:2 Exiting the Quiet Car

Learned Patterns

You find the Hagia Sofia to be underwhelming—they try to sell you on a $50 ticket and the interior doesn’t match your expectations—but across the hippodrome grounds is the Blue Mosque, glowing with the midday call to prayer. Sabrina warned you that tourists aren’t allowed inside during prayer, but you see a flaw in this; you can just enter to pray. You’ve always been Jewish, but Yahweh is Allah, and the city has been a safe haven for Jews for centuries. The least you can do is visit a mosque so grand it drained the Ottoman Empire coffers and see if it was worth it.

Yeah, it really feels like it’s worth it. You add your Blundstones to the skyscraper of shoe caddies and join the hundreds of international worshippers (Detroit, Jakarta, Malmö, Casablanca, the Muslim world is massive). But you do not know what to do with your body when prayer begins. Worshippers are getting low, so you lower yourself. God is great, god is great, the imam repeats. You shadow those in the main prayer area, even though your view is obstructed. Someone taps your shoulder. It is the young man beside you, here with his father. Neither of you speak, but he begins to teach you the motions. Here is how to fully prostrate yourself, touching the carpet with your oily nose and forehead. Here is how to position your hand when you cross your arms. Now sit here as you hear again how god is great. Now rise.

You pray for specific things you only tell Gabe Miller about. You try to greet God in this building, made easier by the ambient interior awe. When prayer ends, you shake the hands of your neighbor and his father. “As salam alaykum,” you say, and are returned with wa alaykum salams. This is one of the most heartfelt moments in your journey.

Limits

Did you forget to mention you took a ferry across the Bosporus to another continent? You roll the sentence around in your mouth like a butterscotch. You were living in Europe, but your final hostel is in Asia. And the Turkish bathhouse near your hostel is listed as “raw, local, and cheap.” $15 for the works. Rick Steves teaches you the word for “slow down” if the masseuse is too intense, but writes that “ouch” is pretty universal.

Alongside the Blue Mosque, it is one of the best buildings you’ve entered in Turkey. Everything inside looks like it was added in the summer of 1951 and left unchanged. The million blue tulips adorning the tiles of the sauna. The nine heavy, Spartan basins you use to scoop hot water across your body from plastic cups. The threadworn, aged towels the staff burrito around your wet body, touching you in a way that reminds you of your father. The bathhouse attendant’s firm hand as he repositions you for soaking, scrubbing, or slapping. Even his barrel belly, a few inches from your eyes, which are closed as the layers of soap and oil flow across you. You grasp a new thought there on the tile floor: you enjoy the freedom that comes with giving up control of your body for someone who knows what they’re doing. A masseuse, a physiotherapist, a tailor, the like. Sometimes, you are naked but for your changing room key wristband. For much of it, you are entirely too hot. The air in the basin-room is sopping and you’re itching for escape. “Oh God,” you say to your bathhouse friend, an aspiring travel influencer. “Next week I’m going to Finland. They love the sauna there. How am I going to survive?”

Flower Girl

You liked the look of a certain neighborhood during the day: hot grey foxes, framed paintings sold secondhand, good glassware in the row of cafes. At night it must be where the cool kids hang out, no? You take with you the Croatian farmer’s market blueberry raika, your hand scanner, and your bag of Bulgarian rose petals picked yesterday, intending to use all three. The airport won’t let you board with the raika, so you nurse the bottle empty on the steps of a grand staircase with a view of Asia beyond you. You are in the territory of countless cats, whose families prowl the streetside obstacles and donated tins of food. You can hear American jocks below you gossiping about hair transplants.

The neighborhood is full with as many cool kids as you expect, which makes you feel like you’ve caught something. You sip a $6 glass of mineral water all night and meet a group of antifascist yoga instructors, a former Fulbright scholar you spot a mile away, and two friends who look like good Brooklyn Jews. They’re Istanbulites, but one spent a year downstate. “I go to Weehawken,” he says with pride. You mingle on the sidewalk, and at dramatic points in the conversation you reach into your bag of rose petals and throw a handful into the air. Everyone likes it, except for the bar staff, who come out with a broom and dustpan to remove any rose remains from the outdoors. By the end of the night you are uncomfortably crouched on a stoop, but you deal with it because you’re talking to an Indian doctor, swapping stories about times you both lowered your standards for love.

“I was the ‘other woman,’” the doctor says. “And sometimes he would answer calls from his girlfriend during the boring parts of sex.”

“I’m sorry, the ‘the boring parts of sex?’”

“The parts where he wasn’t doing much.”

“Okay, so like while he’s being fellated . . .”

“He’d be on a videocall with his girlfriend above me, yes. He said he’d have to answer or she’d get suspicious. And they were both Georgian. It was very intense.”

Summarize

In the Istanbul airport, you call your childhood friend from the food court. You’re hyping yourself up to try the Burger King green banana refresher drink, a Turkish exclusive (you back out after realizing it’s $8.40).

“So that’s sort of the end of the trip,” you tell Ben. “Now it’s time to get to my bags and get to Finland.”

“That sounds like a really profound experience,” he says.

“Huh,” you say, which feels like an accurate summary. “Profound is such an interesting word. I don’t know if it’s felt profound. It’s been busy. I’ve been figuring out schedules, languages, menus, and trying to write everything down as it happens. I don’t know if I’ve had time to think about what I learned here. Or how it’s been profound.” You promise to give it more thought, when you have time to rest. Strangers have been saviors, every place has been deserving of your attention and appreciation, and you get up to adventures. But those aren’t lessons, because you knew all those a few months ago, they’ve just been further baked into your noggin.

Darker

Your plane out of Istanbul is full of men with brand new hair transplants, red-pink continents across their scalps. Your seatmate isn’t one, he’s just a lad listening to strong house music for a couple hours. You begin to draft the notes that will become these newsletters. “You’re a writer?” he asks. Yes, you are. Does that feel good to say?

He’s a first officer on a private yacht. “Below Deck has ruined yachting. All these greenies join the industry thinking they're going to sunbathe. No, it’s real work.” He hasn’t been sailing on his 40-meter yacht in months, it’s been in Leiden’s shipyard getting a 1.8 million dollar paint job.

“What color is it going to?” you ask.

“Grey to midnight blue,” he says, and shows you a photo of a shade that looks like a bowling ball. “Yeah, it’s going to absorb a ton of heat on the lower decks, where the staff are. But the owner thinks it looks nice. It’s different than the rest.”

1:5 Where in the World is Pearse Anderson

You are still in Finland, and glad that you have stopped moving for a while. You are finishing your first two weeks at an art residency, and you feel like a bit of a fake—although you have done a bit of art here, the majority of the time was spent on these newsletters. Drafting everything from Montenegro to Hamburg takes days and days of you staying locked in, confirming locations and passing phrases, sipping a small black tea in the artist residency living room. You feel like you incurred a debt each time you decided to go out for the night instead of write during your travels, and now this is the era of payment. Each day you think you are closer to covering the present moment.

And you are. You have just finished this portion, and only have to cover a bit of North Europe and the journey to Finland before arriving at the building that currently houses/traps/frees you. Despite the frustrations, you’re glad of your path. You’re glad you took on this debt.

1:6 Square Meal

You find the best activity in Istanbul is to eat and walk.

Smash

Simit, a Turkish cousin to the bagel made with a touch of grape molasses, you can’t throw a stone in the city without hitting a stack of fresh simits. For your first, you pick a bakery staffed with three generations of workers—family, you assume. The grandfather was arguing with them as they pulled the dough and slide them into the oven. Hundreds were stacked in the back, bejeweled in sesame. The middle generation slides you yours, it’s warm, simple, and cheap (20 lira, 0.50 USD).

Boza, a breakfast drink a half step down from flour-thickened gravy. It’s a fermented grain drink, sweet and wheaty like porridge. This is what you tried to chase down in Bulgaria, where people buy liters and drink it throughout its lifespan as it grows thicker and more sour with each day of fermentation. You visit a fourth-generation bozacısı (boza shop) that has been in such long active use that the tiles by the ordering counter have had their patterns worn away, and Attaturk’s personal boza cup is framed behind your table. With the walls lined with glass containers, the waterfalling sounds of the serbeti and lemonade machines, and the silence of the staff and patrons, the bozacısı feels like a timeless meditation parlor. You were warned you wouldn’t like the boza, but you aren’t dissuaded. After trying, you enjoy the spiced liquid and its cinnamon topping. The family besides you brings in their own roasted chickpeas to top their drinks with, and they give you a handful after you show curiosity. It’s like a wizard’s cereal. (🌉)

Pickles from the pickle shop. The cukes and cabbage are different than the ones from your past, but standard day players, and the pickled grapes have real pop and fun seeds inside them. When you visit in the morning, the man behind the counter is dumping water or vinegar into the ocean of pickled options with vigor and casualness, like “Yeah, this is what we do here, dump a bunch of water into our workstation.”

The walnut tahini pastry from Beyaz Fırın was really nice, a recommendation from family friend Oya. Super rich, a kind of thing a regal chaparral elf might breakfast on.

You were almost fooled, weren’t you? You almost got got if you hadn’t listened to the fine details of PBS legend Rick Steves, eh? Steves talks about a kofte restaurant so good that it’s spawned copycat kofte places around it. You’re tired and dehydrated after double mosque wanderings, it’s understandable, you almost walk into the first Sultanahmet Köftecisi you see on the correct street. But Steves told you to go straight to the exact address he mentioned and be wary. The website of the place in front of you is sultanahmet-koftesi.com, which 404s when you search it. Your restaurant is sultanahmetkoftesi.com. You walk on. A few doors down is the real deal. "We are the original," the maître d boasts. Inside, the AC is so powerful your napkin is shaking. Arabic or Turkish documentation covers the walls, framed newspaper clippings and handwritten notes from the 80s and 90s. The menu is tiny, and that builds your trust. You get white bean salad, ayran, a kofte platter with peppers and billowing rolls. The kofte is springy, mouthwatering, some of the best mixed meat you’ve ever had. It's meatballs but it's more. Across from you initially is a goateed Southerner, spooning the remaining yogurt into his mouth. "They don't make yogurt like this in America,” he keeps repeating before trying to calculate the hourly income of a place like this. When he leaves, they place an grandad across from you. Neither of you speak each other’s language, so you sip your yogurts with satisfaction, and point to things on your plates while giving a thumbs up.

You have to peel the roasted chestnuts you get from a street cart, but it’s nice to use your hands and you get a toasty, chewable, soft protein treat. Good to walk and talk, which is just what you do. This is the best use of the word "nutmeat" you’ve ever experienced, and it’s $2.50 USD. At the bus stop as you try to get the last chestnut shell off, someone in your group opens with the question “what do you think happens when we die?”

Turkish ice cream, purchased from a thick magazine of dessert options that spans entire continents (and conveniently leaves out prices). Plain Turkish ice cream is flavored with wild orchid petals, and the floral notes are subtle and rockin’. You are not scared off by the gummy texture. Rarely are you ever scared off by ice cream.

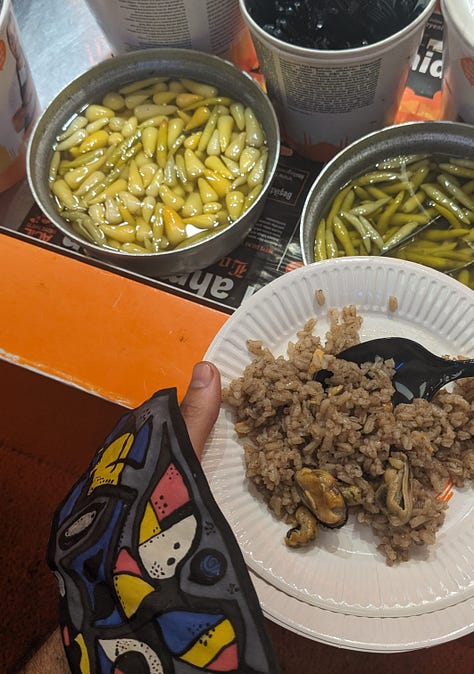

One of your top desired street foods are midye dolma, rice-stuffed mussels. They sound delicious, and often have unhealthy metal/microplastic levels, but doesn’t that describe half the things on Earth now? Midyeci Ahmet Akaretler serves you half their menu, because you order it and because they too respect your curiosity. You approach and ask the first people you can what you should order, you’re new in town. They instantly fall into helping you, translating and menu and pointing at deep bowls of mussels. It turns out that one, Emet, is this location’s owner, and he gets you samples of the stuffed mussels, then rice and mussel pilaf as you wait to officially order. You’re in line with two Azeri men, all of you trying to understand the English menu that still had some untranslated words. You struggled with one. One guy does a stirring motion. The other says "home." Homemade? No. More charades, then: organic. Organic, ah! Organic ayran. The Azeris stick out their hand for a shake, and you put in your order: fried mussel sandwich (fried food with mayo on a white half-loaf, it’s practically a po boy), kokoreç sandwich (lamb intestines stretched across seasoned organ meats; the seasonings really elevate this basic dish and mask any discomfort you’d get at offal), and at least a dozen mussels, regular and sauced (the shells close up with the flavored rice inside, making them a wet game to unlock, but yielding a smooth, filling pocket of sea and carbs when you do). This mussel location is one of many created by Ahmet Çiçek, the “Lord of Mussels,” a viral seafood sensation (a million IG followers) with a booming chain of restaurants (he predicted a 2022 turnover of a billion euros in the last known English-language article). When you take your mussels and sandwiches outside and don your complimentary gloves, you find the man seated next to you has an arm tattoo that reads LORD OF MUSSELS. Every minute or two, someone stops by to take a selfie with him. A passersby gives him candies, and he tells you he’s received jewelry and other gifts almost daily. He films the majority of your interaction, as you put a bit of the “American foreigner” persona and describe your first Turkish dinner, shell and all. And then Ahmet goes back to sitting on the street, scrolling through vertical videos. You are reminded of Diogenes, the famous philosopher who lived in a barrel on the streets of Athens, but this sight seems sadder to you than barrel-bound philosophy. (🌉)

You think Leylak, a very veg/vegan friendly home cooking joint on the Asian side of Istanbul, should take the prize for cheap, delicious cafeteria food. They overcharged you, but you found it to be still reasonable for their spiced couscous, apple/beet salad, stuffed pepper, and a plate of warm green beans with brown bread. The place is full of good people, the chalkboard menu is long. You run into hostelgoers there and eat your plates fast, balanced on a corner of the table as a one-eyed street cat rests on your lap.

Pass

Your first breakfast in Turkey is a train-compartment meal of Montenegrin chicken paste spread across puffed rice cakes as the drunk guy awakens above you. It’s not great, but it’s what had to happen.

Ottoman's syrup, a mix between chai and grape juice. It's cold, refreshing, has listed health benefits beside it, but you find it too spiced, like overmulled wine. You realize that makes you sound very white. You go across the street to Sevda Gazozcusu, a soda shop, to see if their soft drinks would be more appealing—they have everything from cactus to bitter almond. (🌉)

Çiya Sofrası’s sister kebab restaurant seats you 30 minutes before closing, and asks you to leave their outside seating a minute before 10 PM, making you rush to pay the waiter and sort out prices. You’re not hungry when you arrive but order two vegetable-based desserts: one with pumpkin, one with tomato. No tomato dessert. They can do eggplant? You’ll try eggplant. Did you think you were brave for that? What arrives is a plate you could never have predicted. A rib of candied pumpkin, so crisp and jellied that you assume it’s a sugared and molded gelatin dessert. It’s sauced with peanuty tahini and crushed halva. On the other side, beside a mound of clotted cream, are two grenade-like confections stuffed with walnuts where the detonator pins would go. You poke at them. The grenades also look fake to you, also like reconstituted sugar shaped like dates. Your waiter says they’re eggplants. Oh. You keep trying both, but finish neither. Their ability to transmogrify vegetables into desserts is powerful, like a magician’s ability to turn a dove into a deck of cards, but you’d rather be served bird than spades. (🌉)

You really wanted to like şalgam, fermented purple carrot juice, and you grab a $2 bottle as your final Turkish beverage. You know to expect something different, the juice flavored with aromatic turnip and lactic acid/ethanol from fermentation, and you try it twice to make sure you’re clear—this is unfortunately awful for you. There is an unshaking undercurrent of rotten vegetable liquid, scented just like the drippings at the bottom of a compost bucket, that you can’t outrun.

One of those shredded wheat syrup-soaked creations (there’s hundreds of different shapes and ratios), with crushed pistachios covering the filling. But just covering! It’s a facade of nuts placed atop, you guessed it, more wheat and syrup. A cloyingly sweet but fine beginning to your eating, a decision made when window-shopping at a bakery.

KLM will promise you an onboard meal during your journey to Schiphol Airport and then slap down the legally thinnest cheese-and-mustard sandwich they can serve. Even the budget Turkish airline you were originally going to fly asked if you preferred kebab meat or falafel for your sandwich when you booked. You get a bloody mary to drink with the sandwich, attempting to patch the meal into a tomato soup situation. It’s the least sad way you could’ve proceeded.

6:5 Under the Bed

There is nothing under the bed this time.